13 may 2003

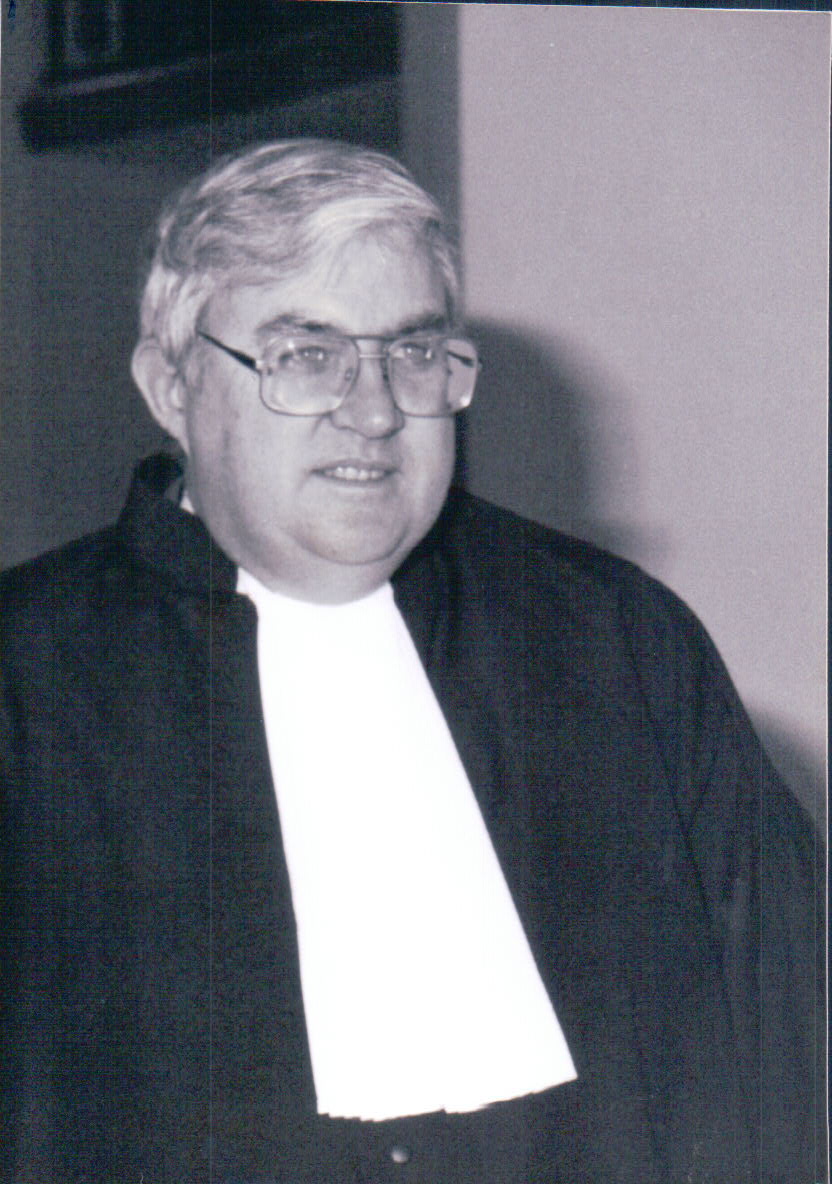

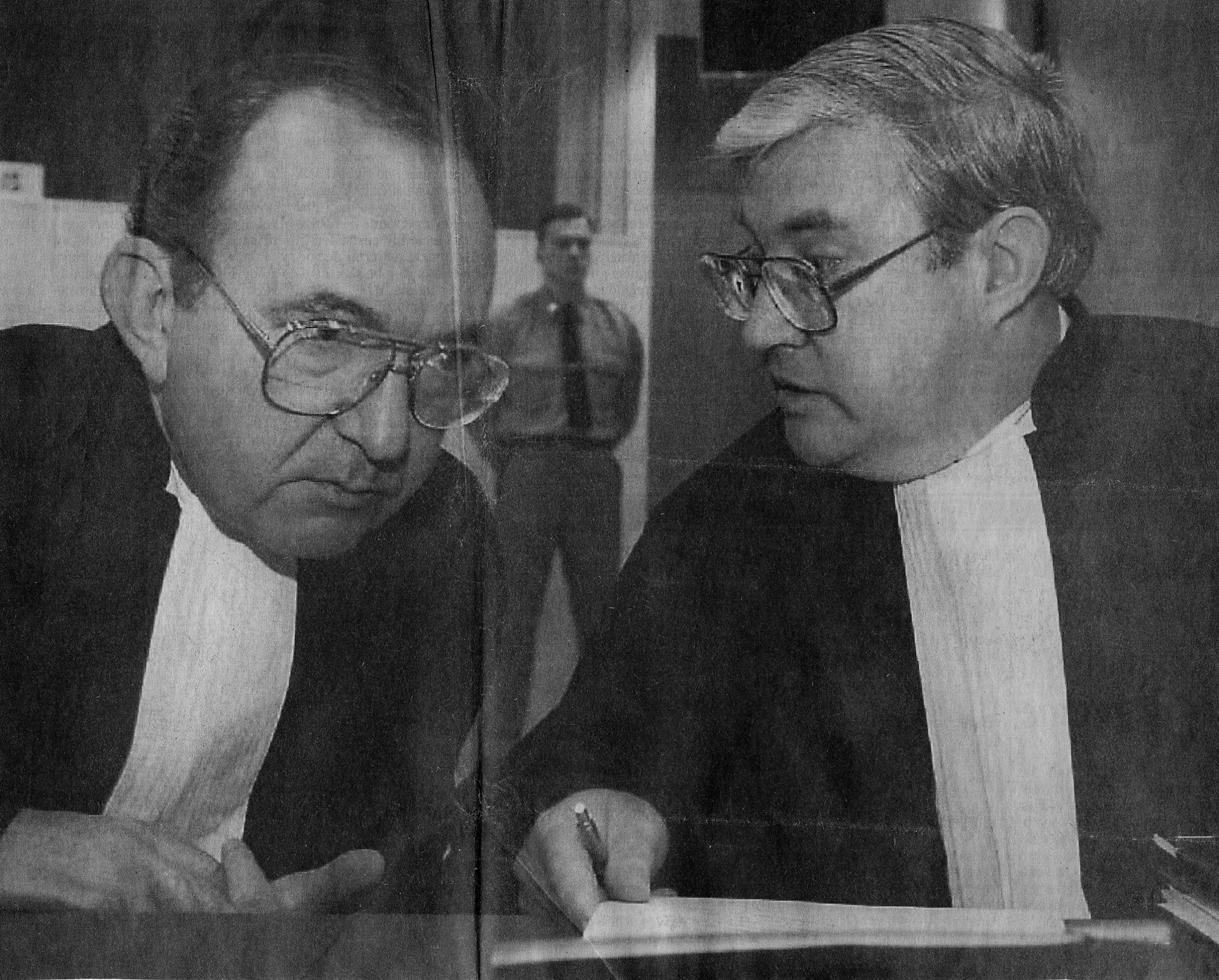

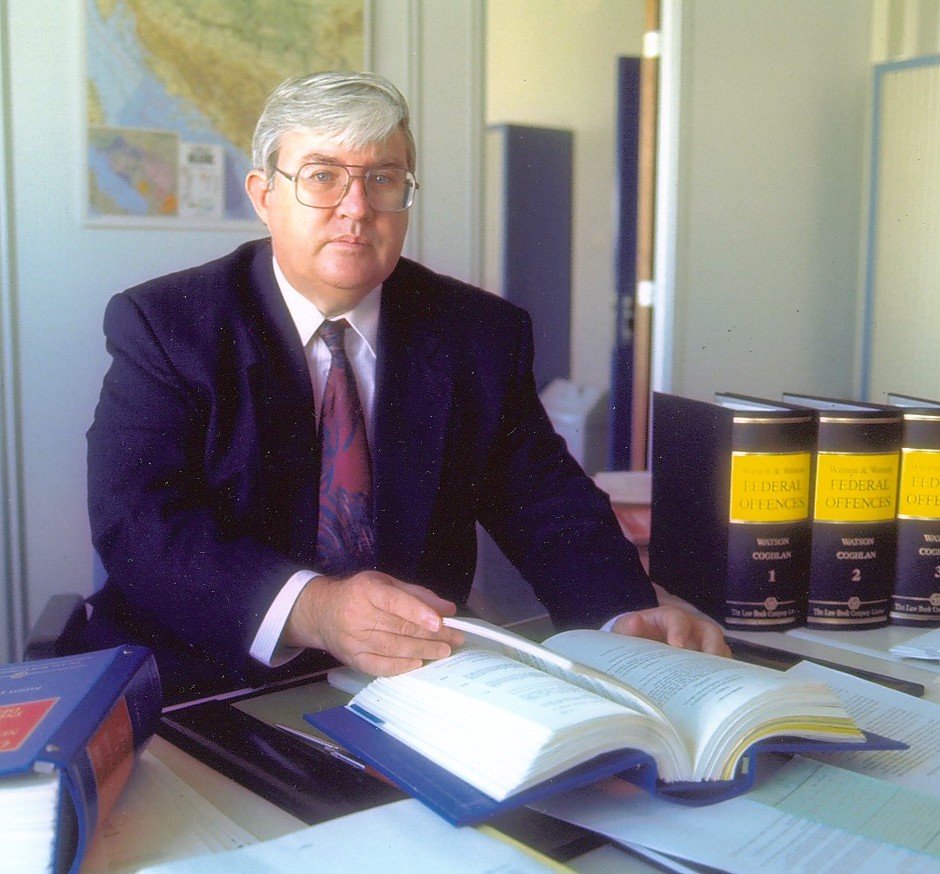

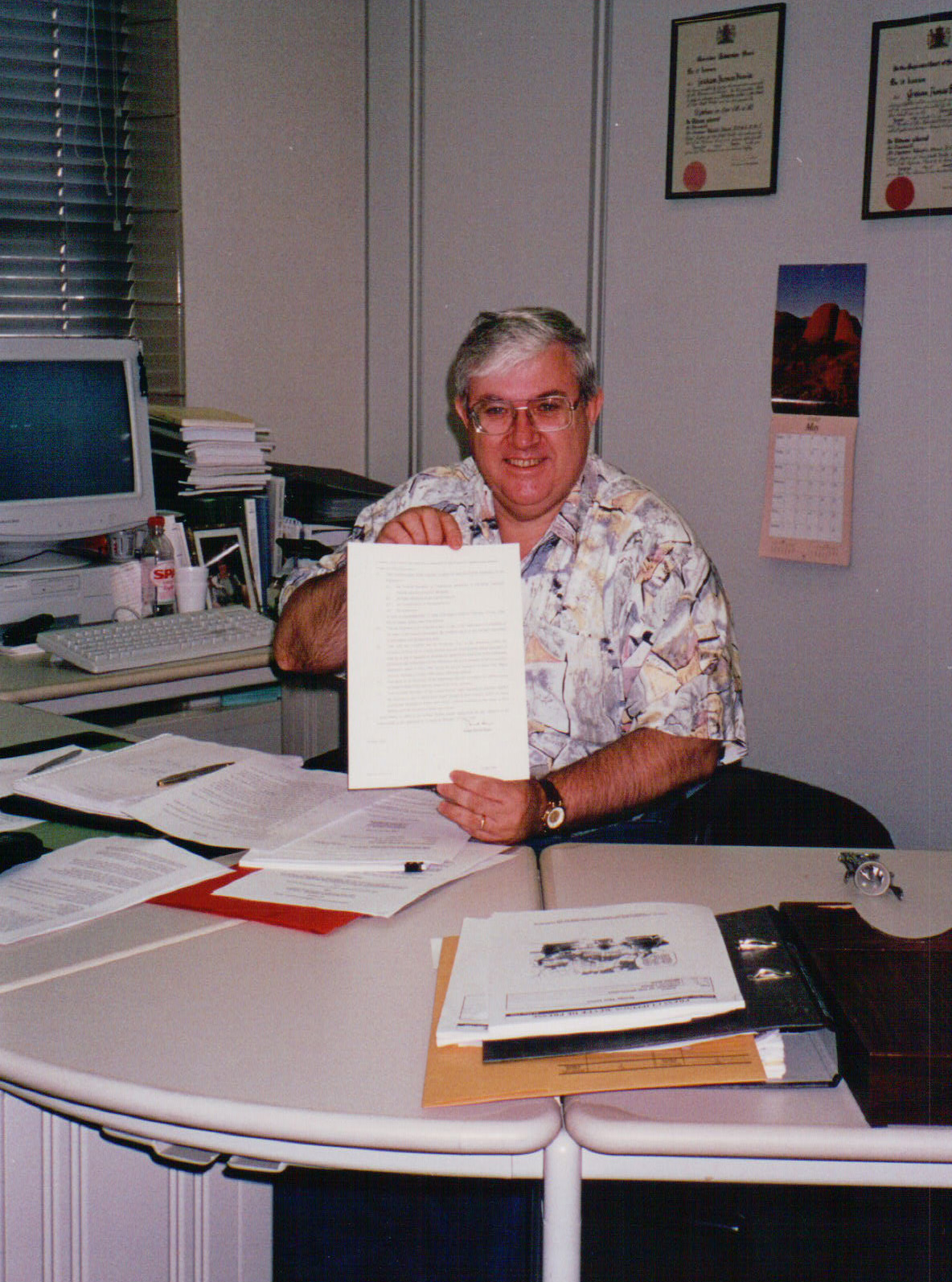

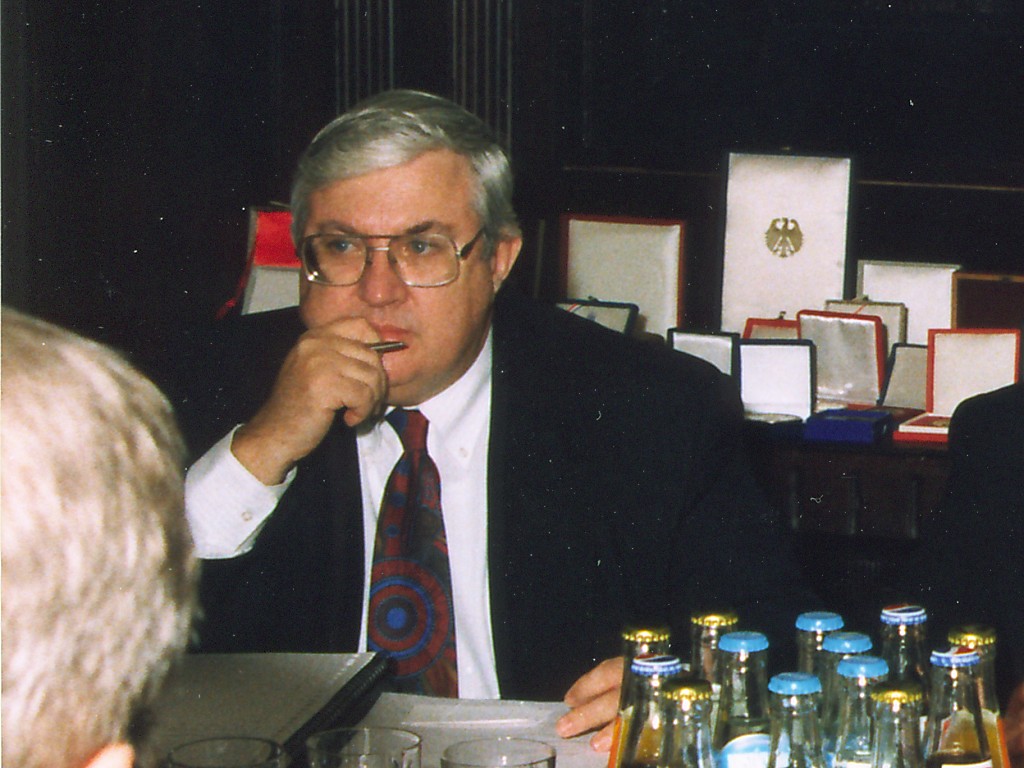

Graham Thomas Blewitt

ICTY Deputy Prosecutor (1994-2004)

Length: 39 minutes

When SFOR realized that World War III wasn't going to start after they started to apprehend people, then SFOR's confidence to proceed with more arrests was just strengthened.

Graham Blewitt, ICTY Deputy Chief Prosecutor (1994-2004), talks about the establishment of the Office of the Prosecutor, the first investigations, indictments, and arrests of indictees. He also reflects on the similarities and differences between the three chief prosecutors he was deputy.

Selected documents

Gallery

Interviews with Graham Thomas Blewitt